Oncoimmunology, Congenital Anemia and Inflammation

The Oncoimmunology, Congenital Anemia and Inflammation lab is a research

group inside of the Hematopoietic Transplant and Cell Therapy group in the

Area 6 of the Biomedical Research Institute of Murcia (IMIB) (https://www.imib.es).

The lab is currently working on several research projects aimed at understanding the molecular

mechanism and inter-relationship between inflammation and congenital anemia.

We are working to find new avenues of treatment for this rare conditions.

What are Congenital Anemias?

Congenital anemias are very complex disorders whose causes are largely unknown

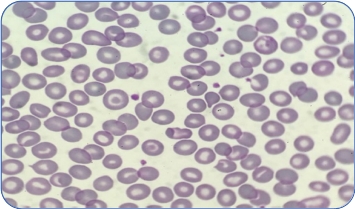

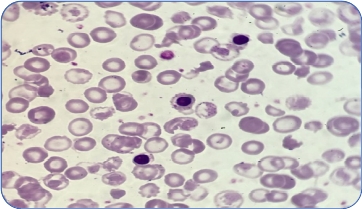

and whose treatments are non-existent or insufficient. The term Congenital Anemia englobes many rare diseases, which have in common a genetic defect that is usually hereditary and affects some part of the erythrocyte.

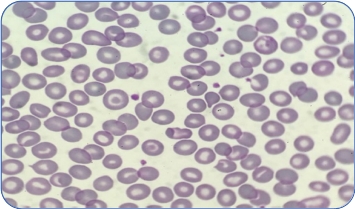

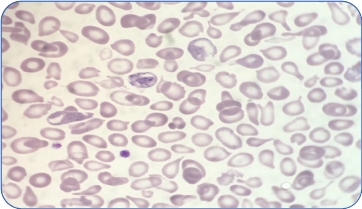

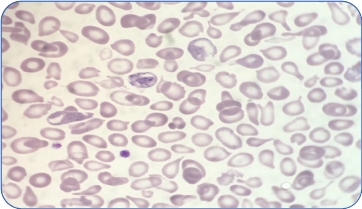

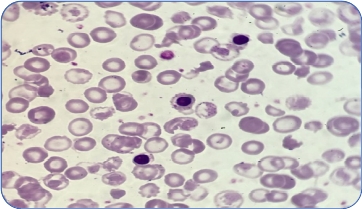

One of the congenital anemias that we are studying is β-thalassemia. β-Thalassemia is a disease caused by genetic mutations that include a nucleotide change, small insertions or deletions in the β-globin gene, or, in rare cases, major deletions in the β-globin gene. The thalassemia carrier state, that is, the presence of a mutated allele, is very frequent in the Mediterranean area and in the Region of Murcia, 5% of the population has this carrier state.

β-Thalassemia has a broad clinical spectrum and has traditionally been clinically classified into thalassemia major (TM), thalassemia intermedia (TI), and thalassemia minor. Patients with thalassemia major group together patients with more severe anemia from an early age who require periodic blood tests and transfusions associated with iron chelation.

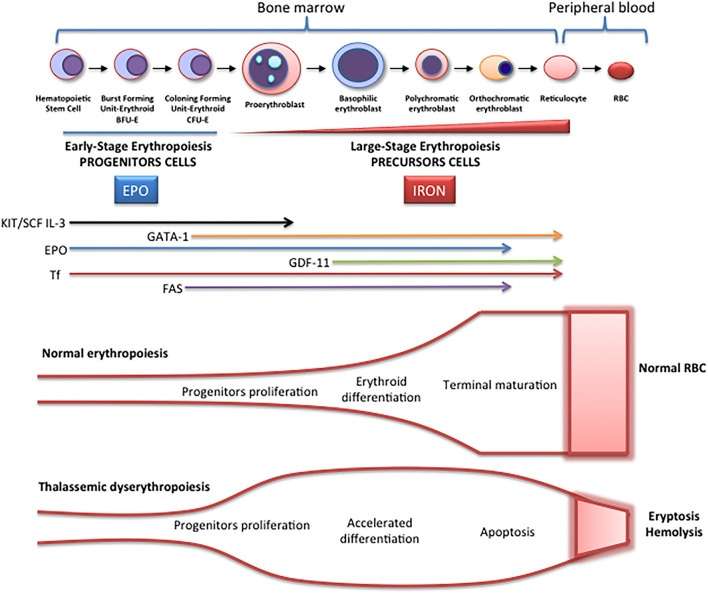

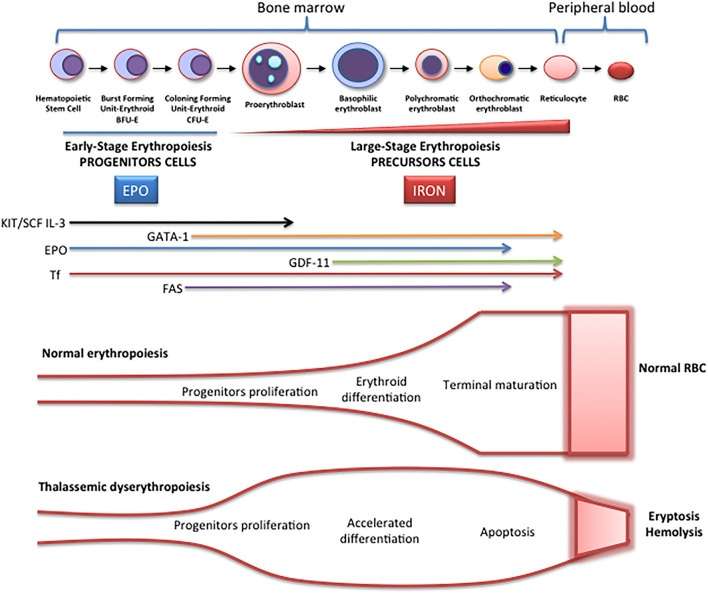

Schematic representation of erythropoiesis. During erythroid development, several stages occur in which a complex network of molecules are expressed (EPO, iron, transcription factors) are involved. In early-stage erythropoiesis, EPO is the main regulator after BFU-E formation. In this stage, GATA-1 promotes erythropoiesis and increases the EPO receptor expression. In large-stage erythropoiesis molecules such as transferrin and growth/differentiating factor 11 (GDF11) are involved. Erythroid expansion is negatively regulated by association of FAS to FAS ligand, which has as a consequence the apoptosis on immature erythroid cells, and GDF11 and other members of the TGF-β family, which negatively regulate erythrocyte differentiation and maturation from the early to the late stages.

Types of thalassemia. Genotype–Phenotype Association. α and β-thalassemias are genetically heterogeneous diseases. The clinical management with RBC transfusions is an essential factor in classifying them as either transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) or non–transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT). Patients with TDT need life-long regular transfusions for survival in early childhood while patients with NTDT do not need life-long regular transfusions for survival and normally have later in childhood or even in adulthood with mild/moderate anemia that requires only occasional or short-course regular transfusions under concrete clinical circumstances during times of erythroid stress (infection, pregnancy, surgery, or aplastic crisis); however, usually present the typical complications of TDT such as extramedullary hematopoiesis, iron overload, leg ulcers, and osteoporosis. Patients with TDT include those with β-thalassemia major or severe forms of β-thalassemia intermedia, HbE/β-thalassemia, or α-thalassemia/HbH disease. NTDT mainly encompasses three clinically distinct forms: β-thalassemia intermedia (β-TI), hemoglobin E/β- thalassemia (mild and moderate forms), and α-thalassemia intermedia (hemoglobin H disease).

One of the congenital anemias that we are studying is β-thalassemia. β-Thalassemia is a disease caused by genetic mutations that include a nucleotide change, small insertions or deletions in the β-globin gene, or, in rare cases, major deletions in the β-globin gene. The thalassemia carrier state, that is, the presence of a mutated allele, is very frequent in the Mediterranean area and in the Region of Murcia, 5% of the population has this carrier state.

β-Thalassemia has a broad clinical spectrum and has traditionally been clinically classified into thalassemia major (TM), thalassemia intermedia (TI), and thalassemia minor. Patients with thalassemia major group together patients with more severe anemia from an early age who require periodic blood tests and transfusions associated with iron chelation.

Schematic representation of erythropoiesis. During erythroid development, several stages occur in which a complex network of molecules are expressed (EPO, iron, transcription factors) are involved. In early-stage erythropoiesis, EPO is the main regulator after BFU-E formation. In this stage, GATA-1 promotes erythropoiesis and increases the EPO receptor expression. In large-stage erythropoiesis molecules such as transferrin and growth/differentiating factor 11 (GDF11) are involved. Erythroid expansion is negatively regulated by association of FAS to FAS ligand, which has as a consequence the apoptosis on immature erythroid cells, and GDF11 and other members of the TGF-β family, which negatively regulate erythrocyte differentiation and maturation from the early to the late stages.

Mild

NTDT

TDT

Types of thalassemia. Genotype–Phenotype Association. α and β-thalassemias are genetically heterogeneous diseases. The clinical management with RBC transfusions is an essential factor in classifying them as either transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) or non–transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT). Patients with TDT need life-long regular transfusions for survival in early childhood while patients with NTDT do not need life-long regular transfusions for survival and normally have later in childhood or even in adulthood with mild/moderate anemia that requires only occasional or short-course regular transfusions under concrete clinical circumstances during times of erythroid stress (infection, pregnancy, surgery, or aplastic crisis); however, usually present the typical complications of TDT such as extramedullary hematopoiesis, iron overload, leg ulcers, and osteoporosis. Patients with TDT include those with β-thalassemia major or severe forms of β-thalassemia intermedia, HbE/β-thalassemia, or α-thalassemia/HbH disease. NTDT mainly encompasses three clinically distinct forms: β-thalassemia intermedia (β-TI), hemoglobin E/β- thalassemia (mild and moderate forms), and α-thalassemia intermedia (hemoglobin H disease).